'I am quite positive we must give the order,' announced a strained Eisenhower to his senior commanders on Sunday evening, 4 June. 'I don't like it, but there it is.' They had already delayed the invasion twice during that wet weekend. But now weather forecasters were predicting a slight break in the spell of bad weather. Eisenhower gave the order to sail the next day; operations would begin on Monday evening: 'I don't see how we can do anything else.' For the people of southern England, who looked up from their gardens and fields on Monday evening and Tuesday, it seemed as if the whole world was on the move.(1945: The War That Never Ended

The soldiers had been living in camps, separate and solitary places, the perimeters of which were marked with posters: 'Do not loiter. Civilians must not talk to army personnel.' With every day and every hour they felt increasingly cut off from daily life. They were aware that they were part of a great plan but, not knowing what exactly it was, felt they were just a part of a machine, a number.

There was no singing on the boats that crossed the Channel. Doug Halloway of the 49th West Riding Division (the Polar Bears) found himself on a ship crammed from top to bottom with equipment, mainly vehicles and guns; sleeping quarters were confined to amidships; 'the floor was covered with palliasses with no space between them, and above was about the same amount of hammocks.' Each sickening lurch brought up a heap of yesterday's bully beef and cabbage. 'I think', said Ronald McKinlay of the RN Commandos, 'one of the main reasons why Normandy was a great success was that the soldiers would much rather have fought thousands of Germans than go back into those boats.' On some American ships swing music was repeated throughout the night; it was still playing over the loudspeakers as the troops went into action.

[...]

Over the next two and a half months Normandy was the focus of the world. Bomber crews would look down in amazement upon the Channel now converted into a vast,living conveyor belt of ships and minesweepers sailing back and forth; like stanchions, destroyers and corvettes were moored on either side of the sea lane, their guns scanning horizons for enemy boats and aircraft. The beaches formed a mere prolongation of the sea, and the land behind it a mere extension of the beaches: a great flat expanse, the plain of Europe.

By Gegor Dallas :127-128)

The view from the ground,

Lt. Col. Robert Wolverton Commander, 3rd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry, June 5, 1944(Utah Beach: The Amphibious Landing and AirborneAlthough I am not a religious man, I would like all of you to kneel with me in prayer. . . . That if die we must, that we die as men would die, without complaining, without pleading, and safe in the feeling that we have done our best for what we believed was right.

Col. Frank Krebs, commander of the 440th Troop Carrier Group at Exeter, conveyed Wolverton and his command team to Normandy on Stoy Hora, the lead C-47 of a forty-five-ship serial. A BBC reporter named Ward Smith accompanied Wolverton's stick and filed a report when he returned to Exeter with Krebs that morning.

Ward Smith Reporter, BBC, June 1944I shall never forget the scene up there in those last fateful minutes, those long lines of motionless, grim-faced young men burdened like pack-horses so that they could hardly stand unaided. . . . So young they looked, on the edge of the unknown. And somehow, so sad. Most sat with eyes closed as the seconds ticked by. They seemed to be asleep, but I could see lips moving wordlessly. . . . The time had come. We were over the drop zones. I wish I could play up that moment, but there was nothing to indicate that this was the supreme climax. Just a whistling that lasted for a few seconds-and those men, so young, so brave, had gone to their destiny.Wolverton's combat career lasted only an instant. According to comrades who jumped from his C-47, the enemy shot him as he descended just east of St. Come du Mont, and he was dead by the time his chute deposited him on the ground. That Drop Zone D was a particularly perilous place for a parachute landing on D-Day was corroborated by the nearly identical fatalities suffered by many of Wolverton's men, including his second-in-command, Maj. George Grant, and the CO of Company G, Capt. Harold Van Antwerp. Furthermore, shortly after the drop, the Germans captured Wolverton's three remaining company commanders, including Capt. John McKnight of Company I.

Capt. John McKnight Commander, Company I, 506th Parachute Infantry, 1947Apparently the Germans anticipated that the invaders might use this area for just such a purpose, and they ringed it with machine guns and mortars, and were sitting at their arms in readiness when the 3rd Battalion came in. . . . Floating down into this well-lit and fire-covered area, the battalion lost about twenty men from enemy action before its first groups could collect themselves.

Operations on D-Day June 6, 1944

By Joseph Balkoski :134-135)

The view from home,

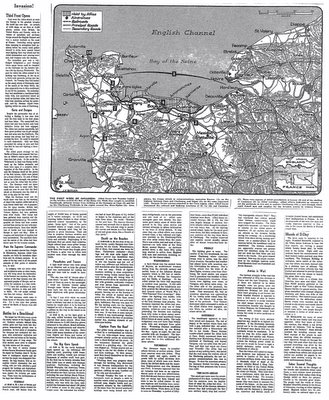

(Invasion!

The New York Times; June 11, 1944 pg. E1)

No comments:

Post a Comment