Notice how the abolitionists invoked the mental metaphor of spiritual war, I've noticed that this sort of artistic vision scares people who are being evil to this day.

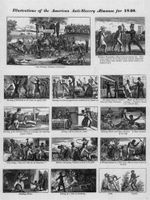

Aboltionist art portrayed slavery as pure Evil:

You might reply, "Portrayed? Why, everyone knows that slavery was evil..."

They think so now largely thanks to people like the abolitionists. But at the time the issue was blurred and people argued, "Well, I know some nice slave owners so how can they make such bad pictures! Why...I, uh, those pictures are just outrageous stereotype!" (There is an emotional and personal argument only focusing on subjectivism to shift away from focusing on an objective sense of Good and Evil.)

Or, "Slaves are better cared for by the slave owners that I know. Why do abolitionists have to be such zealots about it? We need to kick them out of the church because they're scaring away all the tolerant people." (There is the Big Meanie meme, some moral equivalency and shifting to murmuring about tolerance.)

I'm summarizing and updating the language some. Yet I can cite the newspapers in which people make arguments structured like this to demonstrate it. To this day people who pretty much know that they are in the wrong and so supporting evil still make various arguments with the same structures and shifts. It is important to note that back in that day there was tremendous pressure brought against the abolitionists.

Back to the art, the best of which is a fusion of Good common senses and emotions, example:

In matters of art there is but one rule, to paint and to move. And where shall we find conditions more complete, types more vivid, situations more touching, more original, than in Uncle Tom?

--George Sand

______

A parable about honest Abe, a moderate politician who the abolitionists, zealots that they were, had to light the flame of righteousness under.

Abe was honest indeed but he felt like he was being smothered by crushing doubt and a dark despair. He was weakened and sometimes he could only focus on the union...union. The abolitionists were all about justice, principle and righteousness. So even a little lady had more jots to her story than honest Abe wanted to write. Like the other abolitionists she wrote some things about jots and the justice of things. She knew how to put some flesh on dry bones and the telling of stories is a powerful thing to do when they match the patterns of life and appeal to common senses.

So she and the abolitionists lit the flame of righteousness and the nation started to burn!

Now, one day honest Abe met her and said to her, "So this is the little lady who made this big war?"

But she saw the laughter behind his sad eyes and no accusation. He was thanking her. Some moderates need the flame of righteousness to be lit under their butts, after all. In the end, they know it too.

_______

History:

On June 5, 1851, Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly began to appear in serial form in the Washington National Era, an abolitionist weekly. Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery story was published in forty installments over the next ten months. For her story Mrs. Stowe was paid $300.(cf. The Library of Congress)

Although the weekly had a limited circulation, its audience increased as reader after reader passed their copy along to another. In March 1852, a Boston publisher decided to issue Uncle Tom's Cabin as a book and it became an instant best seller. Three hundred thousand copies were sold the first year, and about 2,000,000 copies were sold worldwide by 1857. For one three month period Stowe reportedly received $10,000 in royalties. Across the nation people discussed the novel and hotly debated the most pressing socio-political issue dramatized in its narrative, slavery.

Because Uncle Tom's Cabin so polarized the abolitionist and anti-abolitionist debate, some claim it to be one of the causes of the Civil War. Indeed, when President Lincoln received its author, Harriet Beecher Stowe, at the White House in 1862, legend has it he exclaimed, "So this is the little lady who made this big war?

No comments:

Post a Comment