It is doubtful that Newton would agree with the worldviews and philosophies that have been built on his insights. So ironically, it is doubtful that he would have a problem with possible empirical evidence for that which would be "transphysical." (As defined in reference to his conceptual view of the world.) Instead, it is those who have built their worldviews based on Newtonian physics who seem to have a problem with admitting to such evidence.

Here is some possible evidence for the importance of mind in the little things of life, like dogs that know when their owners are coming home:

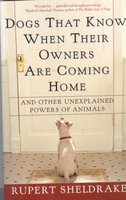

Moreover, Mr. and Mrs. Smart had already noticed that Jaytee [a dog] anticipated Pam’s return [home] even when she arrived in unfamiliar vehicles.(Dogs That Know When Their Owners Are Coming

Nevertheless, to check that Jaytee was not reacting to the sound of Pam’s car or other familiar vehicles, we investigated whether he still responded when she traveled by unusual means: by bicycle, by train, and by taxi. He did.

Pam did not usually tell her parents in advance when she would be coming home, nor did she telephone to inform them. Indeed, she often did not know in advance when she would be returning after spending an evening out, visiting friends, or shopping. But her parents might in some cases have guessed when she would be coming and then, consciously or unconsciously, communicated their expectation to Jaytee. Some of his reactions might therefore be due to her parents’ anticipation rather than to some mysterious influence from Pam herself.

To test this possibility, we carried out experiments in which Pam set off at times selected at random after she had left home. These times were unknown to anyone else. In these experiments, Jaytee started to wait when she set off, or rather a minute or two before while she was making her way to her car, even though no one at home knew when she would be coming. Therefore his reactions could not be explained in terms of her parents’ expectations.

By this stage it was clearly important to start taping Jaytee’s behavior so that a more precise and objective record could be kept. [...] Pam and her parents kindly agreed to do this filmed experiment with Jaytee.

Together with Dr. Heinz Leger and Barbara von Melle...I designed an experiment using two cameras, one filming Jaytee continuously in Pam’s parents’ house, and the other following Pam as she went out and about.

This experiment duly took place in November 1994. Neither Pam nor her parents knew the randomly selected time at which she would be asked to return.

Some three hours and fifty minutes after she had set out, she was told it was time to go home. She then walked to a taxi stand, arriving there five minutes later, and reached home ten minutes after that. As usual, Jaytee greeted her enthusiastically.

From the videotapes, Jaytee’s behavior can be observed in a detail not previously possible. During the period that Pam was out, he spent practically all the time lying quite calmly by the feet of Mrs. Smart. In the edited version produced by ORF for transmission on television, over the period that Pam was told to return, both videotapes can be seen together on a split screen in exact synchrony, so that Pam can be observed on one side of the screen, and Jaytee on the other. To start with, Jaytee is, as usual, lying by Mrs. Smart’s feet. Pam is then told that it is time to return, and almost immediately Jaytee shows signs of alertness, with his ears pricked. Eleven seconds after Pam has been told to go home, while she is walking toward the taxi stand, Jaytee gets up, walks to the window, and sits there expectantly. He remains at the window for the entire duration of Pam’s return journey.

There seems no possible way in which Jaytee could have known by normal sensory means at what instant Pam was setting off to come home. Nor could it have been routine, since the time was chosen at random and was at a time of day when Pam would not normally have returned.

This experiment highlights the importance of Pam’s intentions. Jaytee started to wait when Pam first knew she was going home, before she got into the vehicle and began the taxi journey.

Home: And Other Unexplained Powers of Animals

by Rupert Sheldrake :56-57)

I am no longer in the habit of accepting or simply assuming the "natural" explanation first and treating that as the explanation that supposedly defines whether something is explained or unexplained. For instance, there are some dogs that are known to be able to detect when their owner is going to have a seizure. We could explain that in various ways, perhaps they pick up on a change in body odor and the like. Yet I would not accept that explanation based on nothing but the form of reasoning that has become typical to naturalists: "If we assume that my explanation is true because I call it natural, then it is true!" I.e., you are supposed to accept their explanation as a working hypothesis that is well on its way to being a theory "just like gravity" based on little more than a wave of their hand and murmurings about what science must be limited to according to their own philosophic preferences. It may well be that the dog is picking up a change in body odor, yet one should not accept that explanation by assuming it is so as a matter of first principle or give it any preference based on philosophic naturalism or what passes for "naturalism" these days. In so much as it is an actual and conceptual idea, philosophic naturalism can be tested against the empirical, the logical, etc. The main problem is that it is not an actual idea and more just vague murmurings that include all that is in terms like "natural."

No comments:

Post a Comment